Hello everyone, I hope you enjoy this week's episode. In order to continue to keep the show hosted, we rely on the support of listeners like you. If you'd like to support the show, you may do so here and gain access to premium content for just $1.99 per month, just the price of a couple gumballs. Click

here to support the show. Unfortunately, there is no premium episode this week, but you can still listen to all previous premium episodes. I have to wrap up my semester and have thus been busy. The semester is ending soon though, and premium content will return soon.

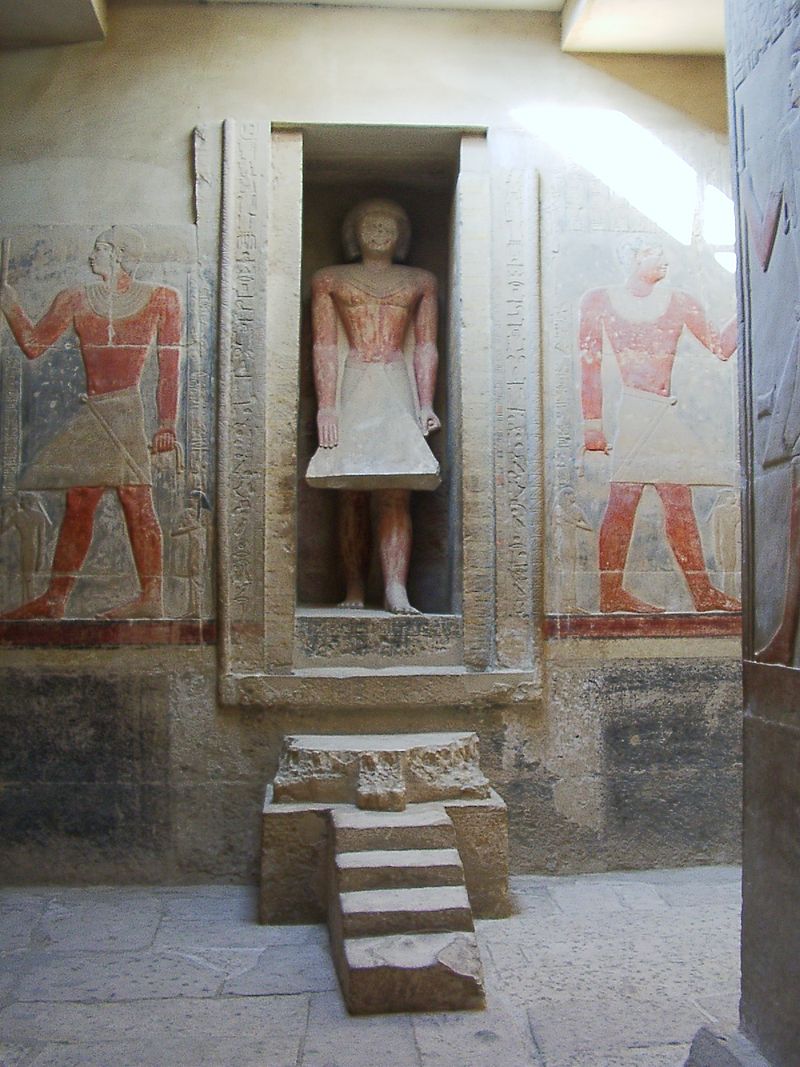

Part of the reason why the Fifth Dynasty is so unknown in popular consciousness compared to its successors is that most of their monuments have no stood the test of time. Above, for example, is Userkaf's pyramid, which lies in ruins at Saqqara (you can see Djoser's pyramid on the right side of the image.) This would become a trend among fifth dynasty Pharaohs, with all of their pyramids either collapsing or remaining unfinished.

Neferirekare's pyramid is the closest to being intact, but even then the rushed structural integrity led to structural problems, and much of the base of the pyramid has collapsed.

During the episode, we talked a bit about the city of Iunu, the origin of the worship of Ra. This city, more commonly known as Heliopolis, remained a religious center long after the solar cult's decline from prominence during the late 5th dynasty. As a token of loyalty, the Egyptian kings of the fifth dynasty routinely offered the Cult huge tracts of valuable land to be used for the cultivation of plants used in rituals. The priests did grow these plants, but they also became incredibly rich as agricultural landowners. Part of Djedkare's motivation in disempowering the Cult of Ra may have been in an effort to reclaim this valuable land from the clutches of the priestly class.

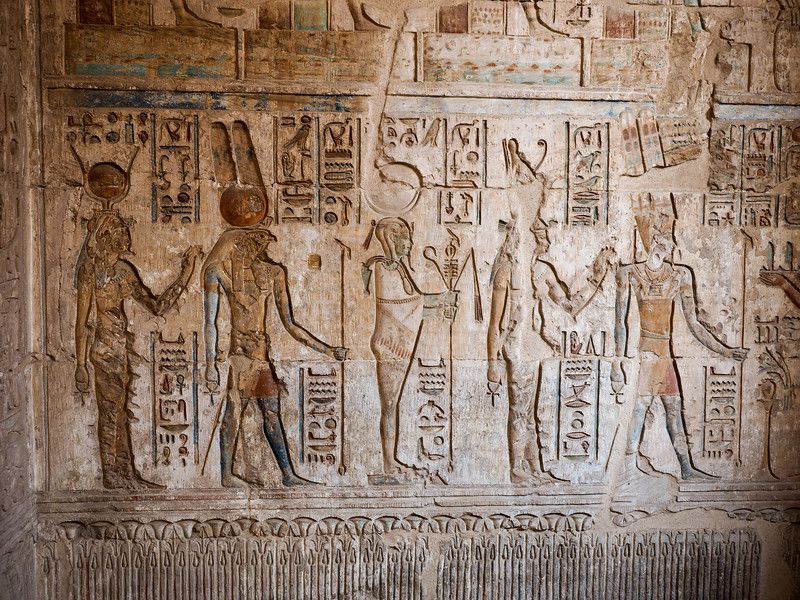

Another thing we mentioned during the episode was Ash, the god of Oases. Ash was a minor deity in Egyptian religion, and was believed to be responsible for the creation of oases Like in many other polytheistic cultures, Egyptian religion usually followed the structure of having major gods that covered a large overarching topic, like Ra, Seth, Neith, as well as minor gods to cover more specific things. Ash, as the god of oases, was associated with Seth, the god of the desert. As the nomadic tribes and city-states of ancient Libya largely focused around the oases that dotted the arid landscape, Ash also became associated with the people of Libya. Ash may even be an Egyptian reimagination of a god worshipped by the people of Libya, or perhaps just another name for Seth himself, meant to represent a more benign aspect of Seth's character. Unlike most Egyptian gods, Ash was portrayed with multiple different animals as his head in artwork from the time, including the head of hawk, vulture, and mythological Seth animal. In the episode, we hear Ash grant the pharaoh Sahure domain over Libya. Like is common throughout the world, Egyptian kings used religion to justify their conquests.

Thank you to friend of the show @loogatwo on Instagram. He provided an excellent voiceover for Ash.