|

In the modern era, Abura has merged with the nearby town of Dunkwa, and is a small town in South-Central Ghana.

|

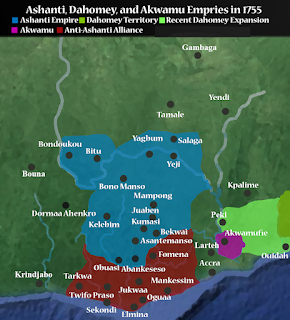

The latest podcast episode followed the foreign policy of the asantehene Osei Kwadwo. As we'll see throughout this episode, Kwadwo's foreign policy strategy involved a stronger emphasis on diplomacy and craftiness instead of brute force. Particularly, Kwadwo often used the tactic of diplomatically isolating his enemies, making them easier to conquer, while cultivating alliances when strategically advantageous.

Ashanti foreign policy had been a mess under his predecessor, Kusi Obodom. During his predecessors rule, many of the empire's peripheral provinces, including the southern states of Akyem, Wasa, and Twifo, as well as the northern vassals of Bonoman and Dagbon slipped away from Ashanti influence. This left the Ashanti in a difficult position, as now both of their primary avenues for foreign trade were commanded by hostile states. To make matters worse, any attempt to reconquer the southern breakaways would be difficult, as the breakaway states had aligned with the powerful southern confederation of Fante. However, this southern alliance would not last long. The allied states really only shared one thing in common - their mutual fear of the Ashanti, but apart from that the interests and needs of each state varied.

The rupture in the southern alliance that Osei Kwadwo would take advantage of arose when the Wasa kingdom of the southwest reignited its practice of raiding Fante border towns. While minor at first, this eventually became a large enough problem that some in the Fante state were convinced that the Wasa were a bigger threat than the Ashanti. The Fante were generally divided into two factions: a pro-Ashanti party, led by the king of Mankessim (the de jure head of the Fante alliance), and the anti-Ashanti party, led by a man name Kwegil. Kwegil was the head of the Asafo military companies of Fante, meaning that he was the de facto military leader of the confederation. In 1765, two Ashanti noblemen arrived in the Fante town of Abora. They claimed that they were there to negotiate an alliance, and would stay as hostages as a sign of good will. Despite initial suspicion, the Fante ultimately agreed to an alliance with the Ashanti to deal with the Akyem and Wasa. At the end of the year, both countries invaded the Akyem kingdom, with the Akyem king becoming a Fante prisoner. However, when Ashanti armies moved suspiciously close to the Fante border, the alliance between the Fante and Ashanti almost immediately broke down. The Asafo companies mobilized to meet the Ashanti near Abora, with the two engaging in a standstill. The Fante didn't want to fight the Ashanti, while the Ashanti were worried that the start of a new war could result in the execution of their hostage diplomats. This standstill persisted until 1772.

In 1772, after several years of failure in negotiating the release of the hostages, Osei Kwadwo settled on a new plan. He would again try to drive a wedge between the Fante and their allies. This time, he sought to drive a wedge between the Fante and their European ally - the British. To do this, he would first need to secure Ashanti access to the sea. In 1772, an Ashanti army marched to Accra, the largest and wealthiest Ga city. There, he offered the Ga an alliance against the Fante, who had become increasingly domineering towards the Ga. The king of Accra accepted. Next, Kwadwo reached out to the Dutch and Danish, the Ashanti's European allies. He asked for them to strongarm the British by pledging support for the Ashanti if war broke out. As a result, the British backed down, convinced that war between the Fante and Ashanti would harm their trade on the coast. Without British support, the diplomatically isolated Fante relented and released the Ashanti hostages.

War between the Fante and Ashanti broke out later that year. In the end, little changed. The Ashanti protected their allies in the Ga cities of Accra and Appalonia, while mounting a semi-successful invasion of the Wasa. Meanwhile, Ashanti armies in the east were defeated by the Krobo, a Ga group which chose to align with the Fante. In 1776, the two sides agreed to peace. With Accra and Appalonia now firmly under their influence, the Ashanti could resume trade on the coast, including importation of firearms. Now that they could purchase firearms again to supplement their domestic firearm industry, the better armed Ashanti army turned north, and reasserted control over the northern territories of Bonoman and Dagbon.

Osei Kwadwo died in 1777. His reign was one of the most successful in Ashanti history, marked by necessary reforms to the Ashanti government and successful ventures in foreign policy. But, despite his successes, his reign would be followed (like many others in Ashanti history) by chaos and infighting. Next episode, we'll focus on yet another Ashanti civil conflict, in which an important noblewoman tries to place her son on the throne, but faces opposition from the richest man in the Ashanti empire.