|

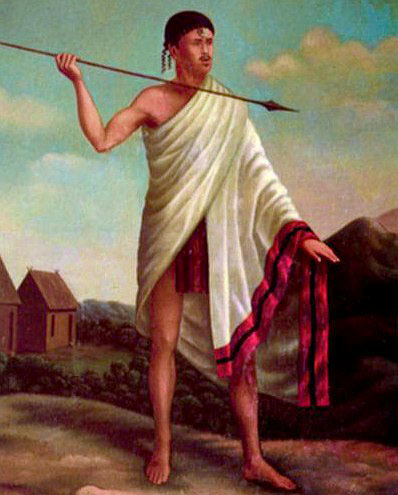

| A 1900 sketch of a Betsileo man in traditional attire. |

|

| Zoma market, for centuries the largest marketplace in Imerina, was one of many markets established by Andrianampoinimerina |

From Aksum to Zimbabwe, Casablanca to Cape Town, learn about the fascinating civilizations and stories of Africa on the first dedicated Pre-Colonial African history podcast.

|

| A 1900 sketch of a Betsileo man in traditional attire. |

|

| Zoma market, for centuries the largest marketplace in Imerina, was one of many markets established by Andrianampoinimerina |

|

| 1905 Portrait of Andrianampoinimerina by Philippe-Auguste Ramanankirahina |

|

| The Rova of Ambohimanga remains one of the best-preserved and most visited Merina historical sites to this day. |

|

| The Hill of Ikaloy, the capital of the Zafimamy Kingdom. |

|

| During this period of civil war, the Sakalava Kingdoms of Menabe and Boeny exploited Merina polities for tribute payments of cattle and slaves in exchange for military assistance. |

|

| The Spanish "Real de a Ocho" or "Piece of Eight", the coins which Rakotomavo sought to mint |

|

| Enslaved man on a sugar plantation in Mauritius |

|

| The old royal residence at Ambohidratrimo, where Andiramasinavalona was held prisoner. |

The 18th century will be a painful time for the people of Imerina. The once proud kingdom will devolve into a deadly multilateral civil war, splitting into dozens of smaller kingdoms, each suffering from intermittent famine and domination by foreign enemies. How could the kingdom of Andriamasinavalona, rapidly rising to become a major player in Madagascar, fall so far. The inciting incident lays at the feet of the otherwise great king Andriamasinavalona.

The mpanjaka Imerina had spread his kingdom several times beyond what his predecessors would have even considered possible. Could such a large kingdom survive in highland Madagascar? Andriamasinavalona believed that the answer was "no." Instead, he favored transforming the Merina kingdom into a confederation of four smaller states called Imerina Efa Toko, or "Imerina like the Legs of a Cooking Pot." The king's advisor Andriamampandry repeated warned him against the plan, cautioning that the newly empowered princes would immediately seek to make war with each other. But Andriamasinavalona persisted.

|

| The public square at the Rova of Antananarivo, where Andriamasinavalona announced the new policy of Imerina Efa Toko |

This policy backfired immensely. Almost immediately upon granting his sons sovereign power, they began quarreling. These early disagreements culminated in the prince of Ambohidratrimo luring the father into his fief by intentionally provoking the ire of his subjects, asking his father for assistance against a rebellion, and then locking his father in a basement when he came to assist the prince. The plan worked for several years, with the prince providing commands supposedly based on his father's wishes. However, the other sons soon grew suspicious, and launched a rescue operation for Andrimasinvalona. While the prince of Ambohidratrimo was defeated and the other sons pledged an oath of peace after their father's death not long after his liberation, the kingdom still fell apart into warring duchies soon after. Join us next episode to see how that goes.

|

| Map of Imerina before Andriamasinvalona's rule (dark green) and at the end (light green) |

|

| An example of a dry (aka upland) rice field from Nepal |

|

| Malagasy locusts, one of the island's deadliest pests. Photo by Peter Prokosch |

|

| An example of terraced rice paddies and an irrigation canal in Imerina. |

|

| Besakana with its original thatched roof |

|

| Interior of Beskana |

In the early 17th century, a raiding party of Sakalava soldiers entered Imerina. King Ralambo, faced with an existential threat, was forced to rely only on a combination of his own wit and divine assistance from the idol Kelimalaza. According to the Tantara, Kelimalaza assisted Ralambo in all of his shocking victories over his larger and better-equipped enemy armies.

The Tantara also describes Ralambo's increasingly strained relationship with one of his sons during this time. While his younger son, Andrianjaka, proved intelligent, dynamic, and brave on the battlefield, the king's relationship with his elder son was far less positive. Andriantompokoindrindra, the elder son, was better known for his gaming addiction than anything else.

|

| A board of fanorona |

|

| Map of Sakalava (green) and Imerina (pink) in the early 17th Century |

|

| A Sakalava woman possessed by an ancestor or spirit during a Tromba ceremony. Sourced from: The Possessed and the Dispossessed by Lesley A. Sharp |

|

| A trio of Sakalava soldiers. Photo captured in 1895. |

|

| The Swahili stone mansions in western Madagascar were close simulacra of Swahili stone houses found on the mainland in settlements like Songo Mnara (pictured) or Kilwa Kisiwani |

|

| Swahili settlement ruins near modern Mahajanga. See earlier photo for comparison. |

|

| An example of an Ody, an amulet used to store hasina from a sampy. |

|

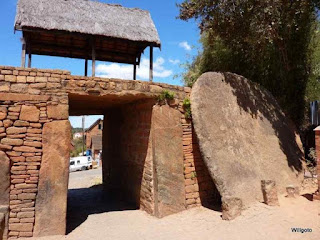

| Fortified gate at Ambohimanga, likely similar to those which defended the settlement from Andriamanelo and his army |

|

| 19th century photograph of the Malagasy circumcision ritual, including blessed water to cleanse the wound |

Andriamanelo is credited with numerous achievements. He expanded the nascent kingdom of Imerimanjaka by marrying the princess of Ambohitrabyby, a nearby city-state. The king is credited with numerous technological and cultural innovations, such as the introduction ironworking technology, the invention or introduction (traditions vary) of Sikidy divination, and the creation of several unique Malagasy wedding traditions.

|

| Sikidy is a form of divination which relies on the use of complex boolean algebra equations. Check out our premium episode about it on our Patreon page. |

Andriamanelo's rule is a difficult period to analyze. While the wide variety of fairly reliable oral histories of his reign generally mark it as "true history" rather than mere legend, the exact achievements and developments of his rule are questionable. Even questions as simple as when Andriamanelo ruled are unknown, while some common elements of his story, like the introduction of ironworking, are outright contradicted by archaeological evidence. Regardless, he is a watershed figure in Merina history.

|

| Andriamanelo's tomb in Alasora |

|

| The tomb of Rangita, located in Imerimanjaka |

|

| Mahafaly statuette depicting a Vazimba, carvdd circa 1960 |

|

| Another Mahafaly statuette of a Vazimba, 1961 |

|

| An example of the type of outrigger canoe used by Austronesian sailors, later introduced to East Africa |

This episode focuses on tracking the settlement of Madagascar by multiple groups of people, including a (possible) short-lived hunter gatherer population from East Africa before 500 BC, followed by the more concretely evidenced arrival of Austronesian and Bantu people in the 6th Century AD.

The status of human settlement on Madagascar prior to the later settlement of the island by Austronesian and Bantu colonization is not especially clear. In fact, it's unclear if there was even a sustainable population of people on the island.

|

| Some examples of the purported tools found at Lakaton'i Anja |

Some archeologists claim that evidence exists to establish the presence of some kind of hunter-gatherer population in pre-settlement Madagascar. While the evidence is fairly convincing, it's not clear as to whether these remains evidence a permanent population or a transient one. The lack of archaeological evidence for long-term shelter construction seemingly indicates that these people may have been transient nomads from the mainland who counted Madagascar among the territories they roamed. Regardless, if such a population did exist by the period of settlement, it was likely small enough that it had a marginal impact on Malagasy history. While some increasingly marginalized theorists believe that there is a link between these hunter gatherers and the semi-mythical Vazimba of early Madagascar, such a link is doubtful for reasons we'll get into in the next episode.

|

| An engraved image of a Javanese ship found at the temple of Borobodur |

There is compelling genetic and linguistic evidence that the bulk of Austronesian settlers in Madagascar were from the Dayak peoples, particularly the Maanyan people of Western Borneo. Different narratives surrounding these Dayak arrivals argue that they were either enslaved workers for a larger Javanese state that sought to use them as labor on the burgeoning settlements in Madagascar, or that they were refugees fleeing the expansion of Indianized kingdoms on their home island.

|

| Example of Tana Pottery |

|

| A (simplified) map of Madagascar's climate zones |

Due to its natural and climactic diversity, Madagascar is sometimes nicknamed the "eighth continent." Despite being a relatively small landmass, Madagascar hosts an unusually varied array of climate zones.

|

| Malagasy spiny forest |

| ||

The unique broadleaf forests of northwest Madagascar. Notice the relative lack of undergrowth. Credit: Damon Ramsey

|

|

| Size comparison between a human, elephant bird, and ostrich. |

|

| Kano, one of the largest cities in the Sokoto Caliphate, pictured in 1860 |

By the 1810s, Shehu Usman Dan Fodio had succeeded in besting many of his enemies. The kingdoms of Kasar Hausa were conquered, while several other neighboring regions were also integrated into the growing imamate. With the "jihad" complete, now the next steps of Fodio's revolutionary playbook were on the agenda. Together with his allies in the Jamaa, Fodio began the steps of creating a society based on his ideals.

The new state that Fodio and his allies birthed into the world was one with an immensely complex political system. Arguably, the Sokoto governmental system is easier to understand if you think of the state as a series of aligned polities rather than a single unitary government.

The head of state and (theoretically) of government was the Amir al-Muminin, or Commander of Believers. This position was intended to be chosen via electoral consensus by the Islamic community, and then serve for life. Of course, Usman Dan Fodio retained his title of Commander of Believers and served as the first leader of the new government. Additionally, to provide his state with further legitimacy and to clarify his mission, the Shehu declared that his new state was a caliphate. In an earlier writing, Masail al-Muhimma, Fodio defined a caliphate as any state governed by someone who sought to act as a successor to the Prophet Muhammad. As a result, the declaration of the Sokoto Caliphate did not represent any attempt by Fodio to position himself as the leader of the entire Islamic world, but rather to state that the mission of his government was to rule in the style of the Prophet Muhammad. Fodio himself rarely even referred to himself as caliph, preferring to retain his old title of Commander of Believers.

The Commander of Believers was largely uninvolved from direct statecraft. Rather, the true executives of the Sokoto Caliphate were the two viziers. The vizier of the west was Usman's brother Abdullahi, who ruled over the regions of Kebbi, Zamfara, and other western regions of the caliphate from his capital at Gwandu. Meanwhile, the eastern portions of the caliphate were overseen by Muhammad Bello from his capital at Sokoto.

|

| Gwandu remains the capital of its own emirate within modern Nigeria. Pictured here is the entrance to the Gwandu emir's palace. |

Each vizier was given the power to appoint a qadi, or judge, for each region, and an emir. The emir essentially acted as the "face of government", performing and overseeing all of the typical responsibilities of the state, such as collecting taxes, enforcing laws, and distributing services. Unlike in the pre-jihad era, where most cities were run by heriditary Sarkis, the emir was, at least in theory, appointed based on merit rather than familial connections. Meanwhile, the qadi was meant to not only oversee judicial functions, but also to ensure that the emir's laws were all within the scholarly consensus of shari'ah.

The nascent caliphate initiated several new sets of reforms, including the creation of a new education system, a grain dole to help poor residents afford food, tax cuts on the working classes, and new regulations to ensure fair trading in the market.

While the Sokoto Revolution may have seemed like an unimpeachably positive development, this was not necessarily true. Even during the life of Usman Dan Fodio, but especially after his death, the state soon began to slip away from its mission of creating a righteous and Quranic society. Perhaps the most visible failure occured in the immediate aftermath of Fodio's passing. While the succession of the position of Commander of Believers was, in theory, an elected one, the Shehu went out of his way to ensure that his son, Muhammad Bello, ruled the kingdom after him. While Fodio argued that Bello was still the most meritocratic option regardless of his descent, the decision set into motion the transformation of the Caliphate into a de facto hereditary monarchy. Almost immediately, Muhammad Bello implemented a series of new policies clearly designed to ward off potential rivals for power. He centralized the military while dramatically increasing its funds, forcing him to raise taxes on the working classes to compensate.

|

| An 1857 illustration depicting a slave raid by a nobleman living in the caliphate |

From a moral perspective, the issues of slavery and militarism forces us to reckon with the otherwise quite positive perception of the Caliphate. The successful conquests of the Caliphate in the south, especially in the former Oyo Empire, produced enormous numbers of war captives. The Sokoto Caliphate maintained the old system of slavery present in Kasar Hausa, involving large communities of enslaved workers concentrated in plantation-esque rural townships. Unlike in some other regions of Africa, slavery in the caliphate was often of the chattel variety, while notions of religious endorsement and psuedo-racialized concepts of "animalistic" southern populations justified the system's existence. In many ways, the economic boom of the early caliphate can be attributed to the system of human misery that underpinned it.

.jpeg) |

| A "slave village" in rural Sokoto |

|

| Map of the Sokoto Imamate at its height |